BUY OR LISTEN

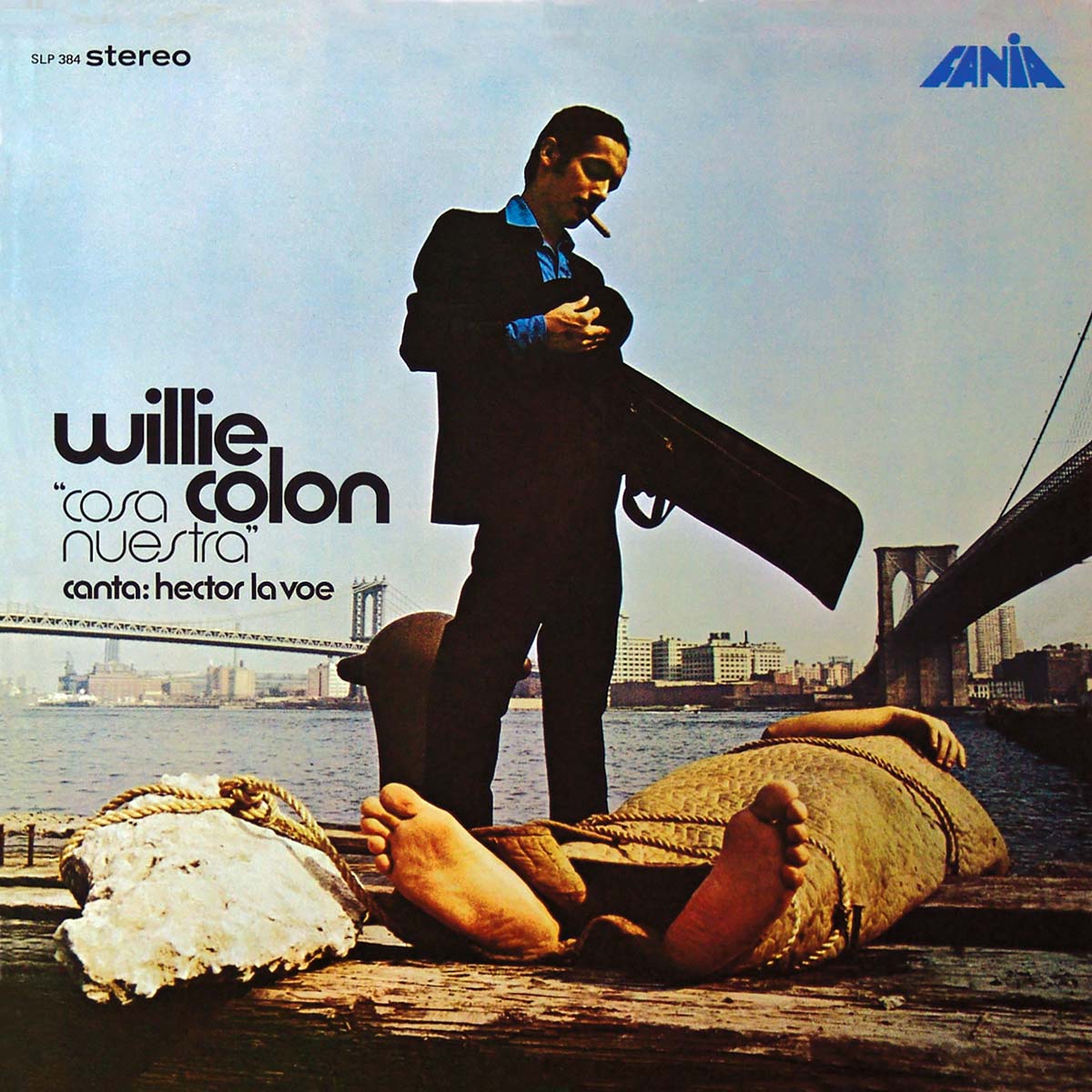

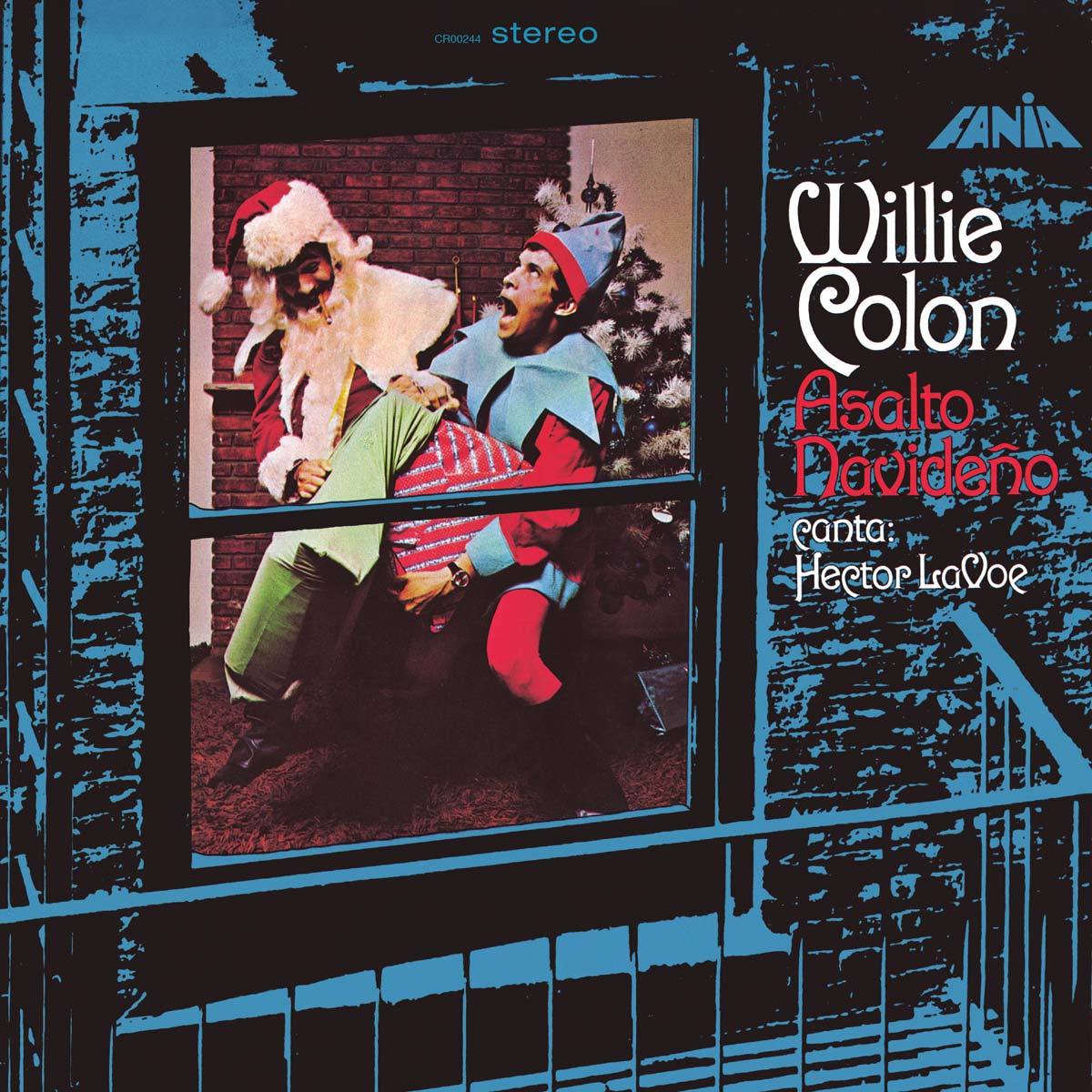

The greatest Tropical Christmas album set ever is now being released for the 2011 season. It’s packaged in a digipack with both volumes of the evergreen classic and original booklets. With Christmas just a few weeks away, it’s time to focus on the amazing selection of Holiday albums that were produced during the apex of the salsa era. From Ismael Rivera and Cheo Feliciano to the venerable El Gran Combo, many legendary artists celebrated the traditions of Puerto Rican Christmas through their own albums. The best one of the bunch, however, is Asalto Navideño, created in the early ’70s by salsa’s dynamic duo, Héctor Lavoe and Willie Colón.

Asalto is one of the most soulful albums ever made by Lavoe and Colón – and it includes the hit single “La Murga,” a staple across Latin American dancefloors. Part of the album’s success can be credited to the presence of cuatro master Yomo Toro, who permeates the recording with the roots of authentic boricua folk. A mandatory addition to any comprehensive collection of tropical music, Asalto Navideño is now available as a digital download. My abuela taught me to respect and appreciate the jíbaro (Puerto Rican peasant) & most things Puerto Rican. The ’50s were an exciting time for Latinos in New York. As a little boy, I loved listening to the old timers sitting on milk crates in front of David’s (Daví) Bodega singing décimas and aguinaldos. It gave me a sense of pride to watch them as they eloquently challenged each other in verse. I loved the fancy words, the quick wit. I wished I could express myself like that. El Ciego (The Blind Man) is the champ of the block. He will take anyone, as Daví keeps the beers coming. It’s the heyday of dance music. The Palladium is rocking. There are many exciting dance halls in the Bronx where you can go all decked out and dance the night away. It’s the magic of New York. The New York Puerto Ricans (Nuyoricans) dance generation finds the old guitar and cuatro music boring.

They mock it, calling it “guilinguín guilinguín” music. There is a separation between the Puerto Rican jíbaros who are into this highly lyrical folkloric music, and the new generation of Nuyorican who barely understand Spanish and who express their Latin identity through their bodies in dance. The name jíbaro has the connotation of a “hick” or “hillbilly.” Being raised by an old school jíbara placed me smack in the middle of this phenomenon. The jíbaros and their cuatros squatting by the bodega next door to my building, and the rumberos playing their congas in the vacant lots and the schoolyard up the block. This is the cultural foundation upon which my life and my career were built. It’s the late 50’s. My mom works at a lingerie shop on 149th street, near Brook Avenue. I walk up to the store after school. It is over a mile away, going through many different turfs. Along St. Mary’s Park, I turn left at the pet shop on the corner of St. Anne’s and 149th. I always stop to look at the animals there before continuing to Maury’s Lingerie. While I’m visiting my mom, a customer walks into the shop. I step outside for a while; after all, buying underwear is a personal kind of thing.

While waiting, I walk a couple of storefronts toward the middle of the block and look into the window of La Campana Bar. I can hear a group playing inside; it’s one of those “guilinguín guilinguín” trios. The sign on the window reads “Friday Nights: Yomo Toro.” I try to peek in, but someone pulls me away so that I won’t see the go-go girls. By the ’60s, with the Vietnam war and civil rights movement in the forefront, the baby boomer rumberos have all but taken over the block. At night, the rumberos put their drums away and go dancing, or listen to the Symphony Sid or Dick Ricardo Sugar radio shows on the stoop. The jam sessions in the schoolyards and parks are more developed now. They are well attended, with all kinds of amateur musicians showing up to play, including myself. I’m around 12 years old. Most of the conga drummers are Puerto Rican. Papín is Cuban and brings a full bass. Fernando is Dominican. He brings his violin. Tijoe is African American; he and I play the trumpet. Guaguancó, bomba, plena. The music represents our spirit and identity. Most of the older guys are gone. Drafted to Vietnam or in jail, mostly for drugs, or dead from one of the two. As the American Apartheid is in its death throes, we watch Martin Luther King marching through Selma on black and white TV. While hostile racist police (minimum height: 6.5’) sweeps our jam sessions for “Illegal Assembly” or “Disturbing the Peace,” we feel part of the movement. We return the following day if the weather and conditions are right. This is our little piece of civil disobedience, in solidarity with the cause. It’s 1971. Héctor Lavoe and I have a string of hits off our first six albums. The jíbaro qualities of Héctor inspires me to try a crazy experiment. I visit Fania president and owner Jerry Masucci, who now believes I have the Midas touch, to pitch him a Christmas Record. I start explaining that it will be a traditional jíbaro Christmas record, when Jerry interrupts me. “Yeah, yeah yeah,” he says. “Just bring me the record. I don’t need to know anything.” I am ecstatic and start preproduction work on Asalto Navideño. Asalto (assault) was the perfect word, since we were already embracing a comical gangsta image. The asalto is a Puerto Rican Christmas tradition that involves being assaulted by a group of carolers. If you don’t have anything to offer, the carolers sing insults to the homeowners for being so stingy. I “move up” into Woodlawn, the Irish area of the Bronx.

Across the street from my apartment are two vacant storefronts. I rent them and unite them into one, bringing in a grand piano, soundproofing and upgrading the space into a rehearsal studio. Marty Sheller lives in Co-op City nearby, and our first project at the studio is Asalto. Marty helps me orchestrate the sketches I wrote for the “Popurrí” (a medley of aguinaldos), “Esta Navidad” and “La Murga.” Héctor helps me finish the lyrics. He acts as my jíbaro connection. I ask him to find some original jíbaro songs, and he brings “Aires De Navidad” by Robertito García, “Vive Tu Vida Contento” and “Canto A Borinquen” both by “Ramito” Flor Morales Ramos. The arrangements are ready, and it’s now time to conduct our first full rehearsal. I call the guys: Milton, Mangual, Professor Joe, Santi, Willie Campbell, Roberto García, Louie Romero. We rehearse late into the night. In the morning, I return and see that the storefront has been wrecked. Must be the gentlemen from the pub around the corner. I call Mikey from the old block, he works in construction. I have him build a brick front with two bulletproof windows. Now that the problems is solved, we can go on with the album. We are finally ready to book the recording studio. I’m listening to Polito Vega’s radio show and he’s doing call-ins. You can sing any song over the phone and Polito has Yomo Toro with him to accompany the callers on the cuatro. I ask Héctor if he knows Yomo. He said Robertito knows him well. We invite Yomo to the recording session.

Word gets out about this crazy idea, and even Polito shows up to the session. It’s like a party. The band is well rehearsed, fired up, ready to make some music. Yomo shows up, and Pacheco is beginning to grasp what’s going on. He asks Yomo: “What are you doing here? Are you recording with Ramito?” Yomo locks with the band as if he had been playing with us for years. Everybody feels the vibe. Polito is excited and wants to get into the act. We ask him to MC the intro to the record while we play a seis chorreao and Yomo strums. Polito slams it out of the park with his improvisations. We all felt that it was something new. But it turned out to be way more than that. Yomo became part of the Fania All Stars and a salsa favorite. Asalto Navideño has been one of the bestselling albums in its field. “La Murga” became an international standard and one of the most recorded and sampled songs to this day. Personally, Asalto Navideño allowed me to reconcile both the jíbaro and the rumbero in me.

Written by Willie Colón

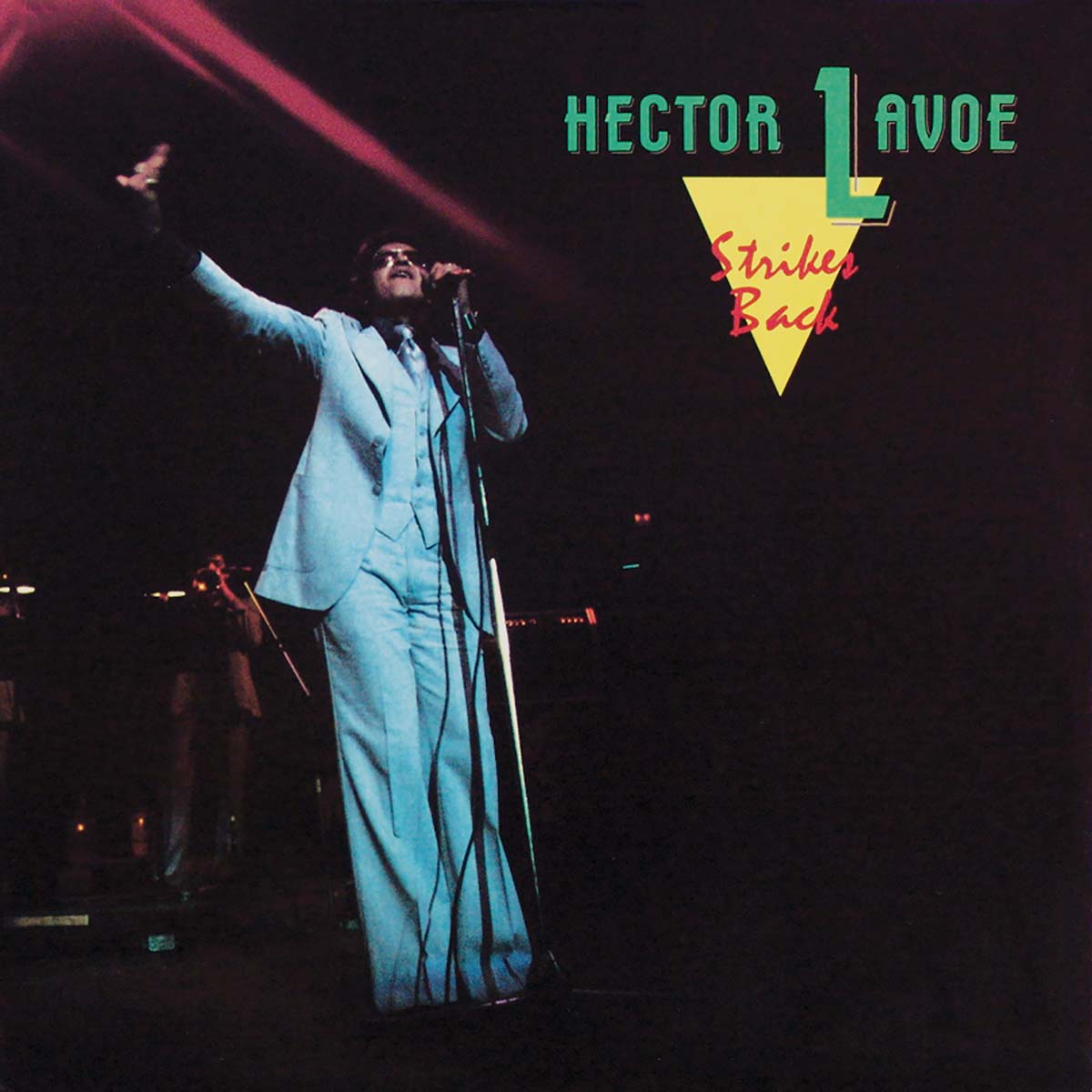

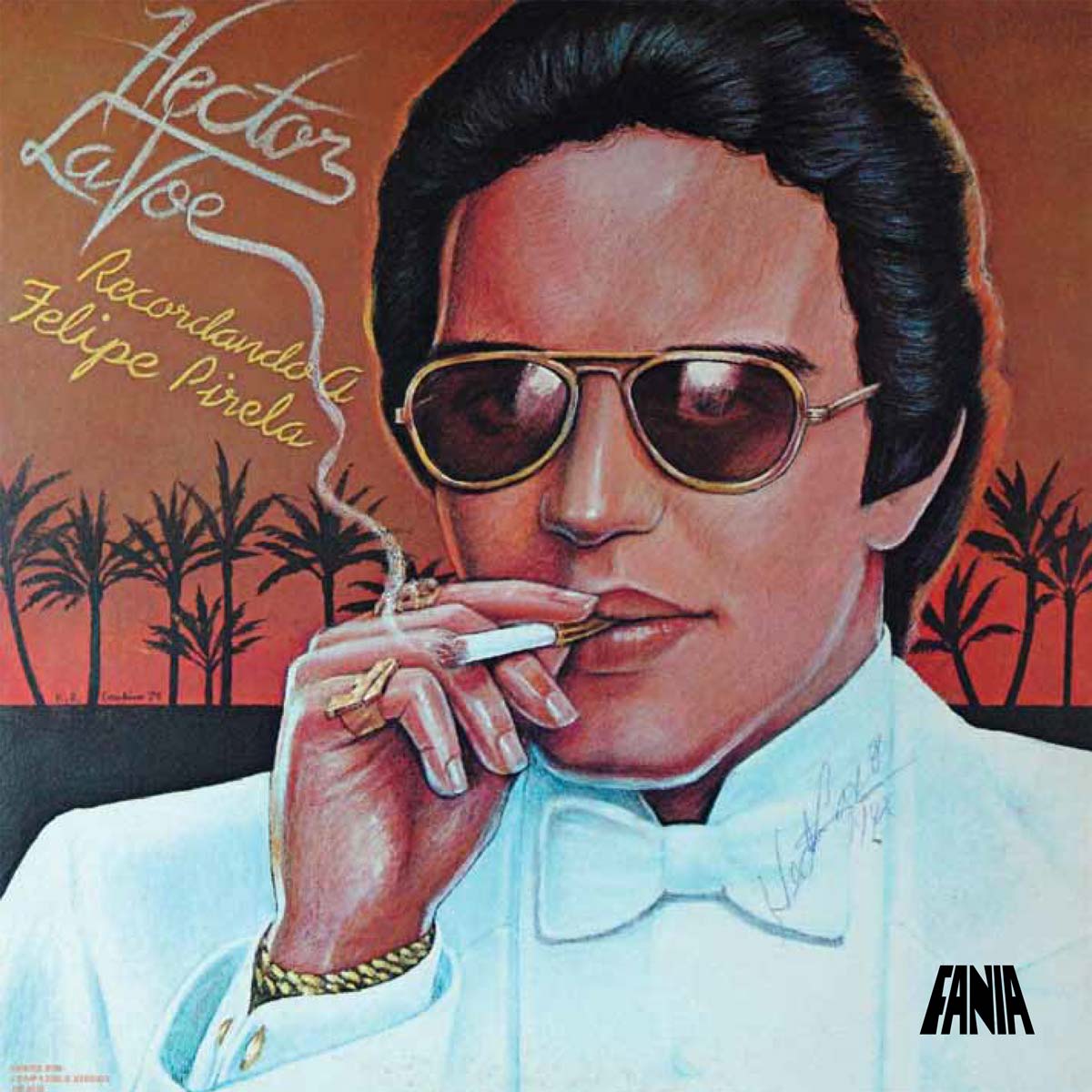

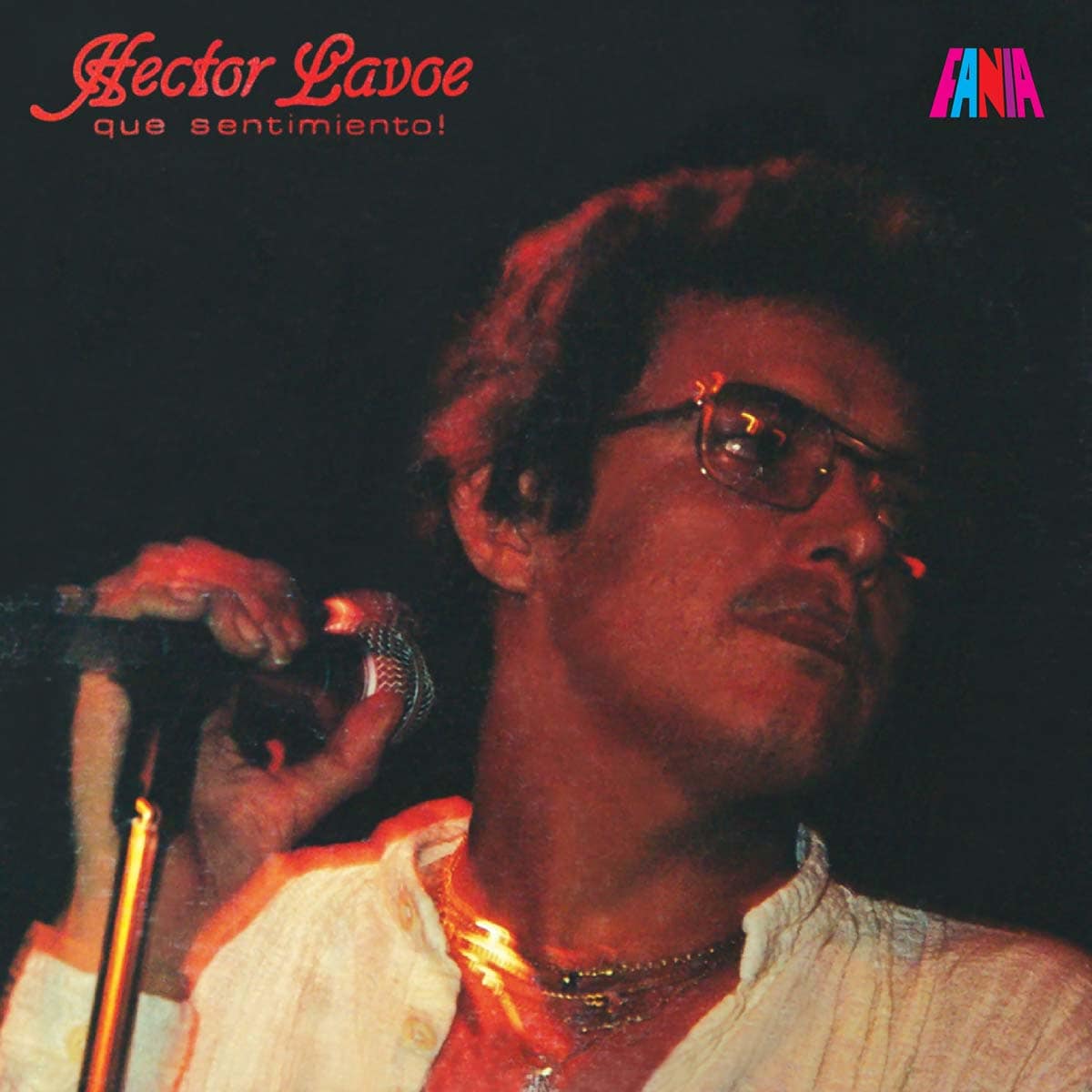

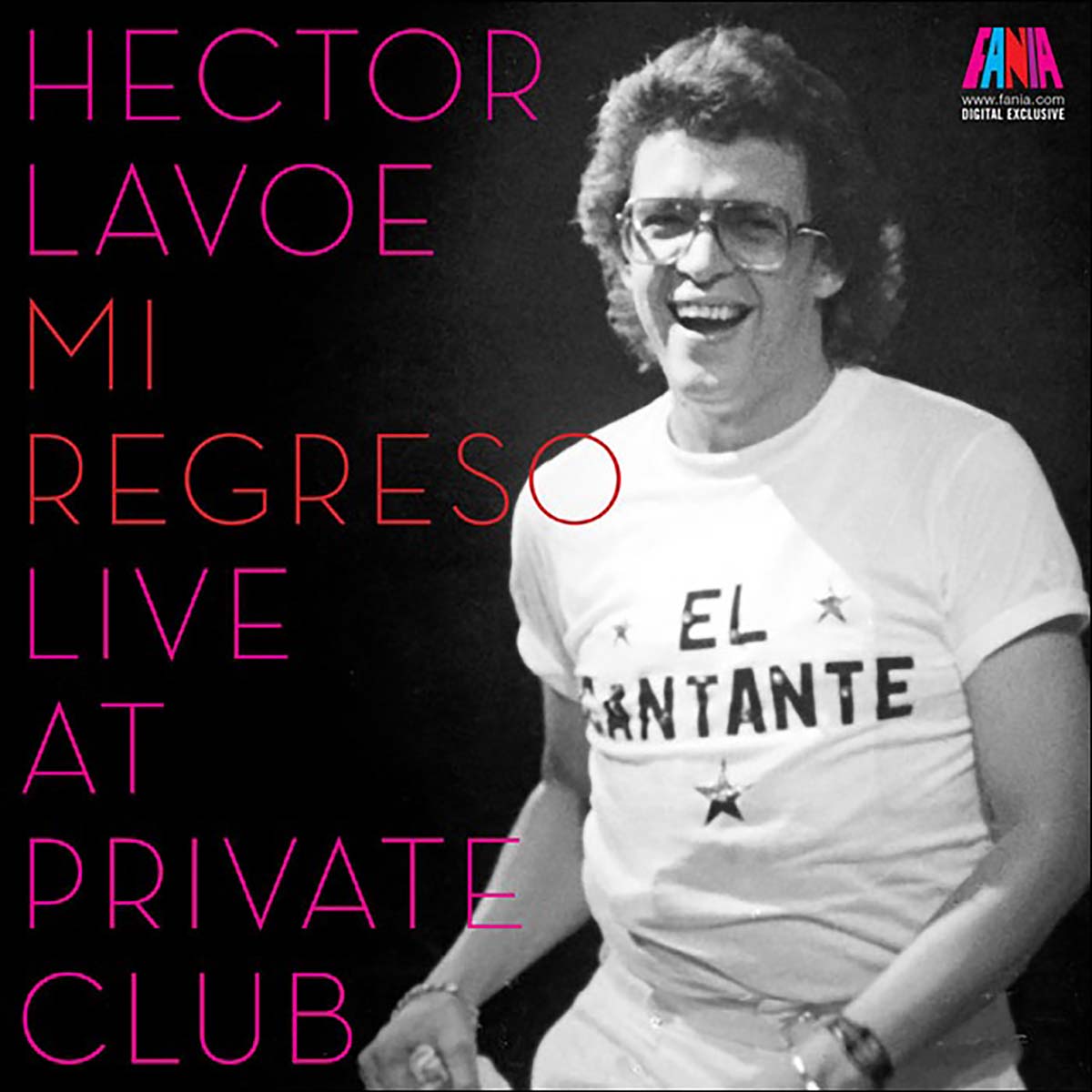

Other Releases by Hector Lavoe

Other Releases by Willie Colón